L'edicola digitale delle riviste italiane di arte e cultura contemporanea

Flash Art Int. (1999 - 2001) Anno 33 Numero 213 summer 2000

Aperto New York

Grady T. Turner

Ringing Cash Registers at the Idea Depot

Franz Ackermann

Wolf-Günter Thiel and Milena Nikolova

n. 216 Jan-Feb 2001

Shangai Biennale

Satoru Nagoya

n. 216 January-February 2001

Aperto Albania

Edi Muka

n. 216 January-February 2001

Cecily Brown and Odili Donald Odita

n. 215 November-December 2000

Cai Guo-Qiang

Evelyne Jouanno

n. 215 November-December 2000

Sexually Explicit Art

Grady T. Turner

n. 212 May-June 2000

By this point it's almost ritual. One critic announces the death of installation art while another points to its vitality. No sooner does one museum director dismiss web-based projects as a passing fad than another declares digital art the most important medium of our era. A curator organises a show to high-light a renaissance of abstract painting, while across town another curator proclaims a resurgence of figuration. What's remarkable about these apparent contradictions is that there's no real disagreement at stake. Fuelled by a surging economy, New York is enjoying a surfeit of easy money and sees no problem in supporting contradiction.

With over 500 galleries spread over a dozen neighbourhoods - from the East 70s to SoHo, from Chelsea to Williamsburg, from DUMBO to Harlem - it is not surprising that even within New York, the local art scene seems to defy the very notion of an art centre. International art fairs and on-line auctions may have challenged New York's hegemony in the art market (while continuing to fill the coffers of the city's dealers), but the city's art scene is too busy churning synergy and ringing cash registers to take note. Local artists have no interest in turf wars or ideological disputes. As a result, for good and ill, anything goes in New York. Such a situation would have been impossible to predict just fifty years ago, when New York was on the periphery of the international art world. From the perspective of Paris, New York was viewed as a provincial cousin allowed to sit at the table though he never seemed quite sure which fork to use. New York's interests were parochial: the city's artists were then charged with developing a national cultural identity, a project that began in the early 19th century when New York emerged as the nation's economic and cultural capital.

Of course, World War II changed all that. Long accepted as the American art centre and port-of-call for European art, New York was well-poised to become the hub of the international art world when Paris collapsed. Since the war, New York has been the place where the first draft of art history is written. Every significant artist, movement, and style has been represented here. As a result, the city gradually put aside its concern with defining nationality through culture, and the world as its purview. In its turn toward the international scene, New York art set itself apart form American art. Though the nation's art capital, the city would rarely concern itself with issues of nationality. This distinction between New York and American art was made once again by a subtle contrast between two recent summaries of contemporary art mounted in the city, each so sprawling that they very nearly split the seams of their retrospective venues. P.S.1's "Greater New York" focused on artists based in the metropolitan areas, resulting in a selection that reflected New York's international mix of artists. The Whitney Biennial included artists from all regions of the country, but clung to the traditional requirement that the artists be US citizens. So it was that many rising stars were embraced as New Yorkers at P.S.1, but not deemed American enough for the Biennial. Thus, while "Greater New York" began with more restricted boundaries, it ended with a more expansive view of the diversity of artists in America. Increasingly since the late 1980s, New York artists have fully abandoned the project of defining the next big thing in American art. Independent to the point of insolence, the current generation of Young Turks, smart alecks, and computer nerds blithely thwarts every effort to define a cogent movement. Having wrested from Europe the authority to pronounce the dominant "ism," New York now pronounces that endeavour to be a huge bore.

The current disenfranchisement of didactism is manifested by the resurgent careers of two artists, Nayland Blake and Rob Pruitt, whose lack of art world pretensions was out of step with the mood of the mid-1990s. Pruitt was perhaps the worst offender: together with his partner in the art team Pruitt and Early, he was castigated from displaying racist tchtotkes in an installation. Such misbehaviour was intolerable in the political climate of the 1990s. Today, it seems prescient of the "bad boy/bad girl" subculture in art.

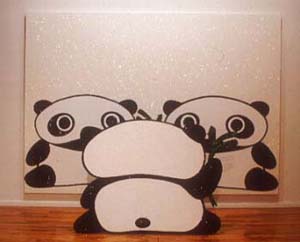

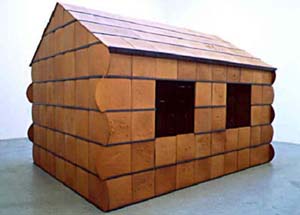

Kitsch and subversion remain important elements of Pruitt's work. Last year, Pruitt filled Gavin Brown's Enterprise with a garage full of stuff illustrating his "101 Art Ideas." Following Pruitt's example, anyone could be a do-it-yourself conceptual artist. For example, try drawing yourself into your favourite comic strip, as Pruitt did in a wall-sized mural of him and his pet chihuaha among the "Peanuts" gang. Or lay in bed all day watching a television placed on its side; Pruitt provided the furniture to try it out. Tape a paper leaf to a tree, point an exercycle at an abstract painting, decorate your refrigerator with Stella-esque racing stripes - Pruitt found no shortage of art materials around the house. At P.S.1, Pruitt exceeded even Jeff Koons's infatuation with the aesthetics of cutesiness with two oversized sculptures of animé - inspired panda bears plopped before a glittery painting. Blake similarly takes inspiration from homey knick-knacks and childhood artefacts. His art is suffused with wit and play, but it can be discomfiting, as Blake subjects his work and himself to bouts of intense psychic scrutiny. His two most recent solo shows at Matthew Marks featured gingerbread houses, one large enough to enter. The resolent aroma of gingerbread was immediately evocative of home and hearth, warmth and nurturance. But there were creepier associations as well that were brought out by accompanying videos. In last year's show. Blake sat shirtless and passive as he was forcibly fed watermelon by a black man. In the recent exhibit, Blake appeared in an oversized bunny suit weighted with the equivalent of his boyfriend's 146 pounds. With considerable difficulty, he obeyed his boyfriend's off-screen commands to dance, turn, and jump. All of which sounds silly, and perhaps it is. But it resonates on a deeply personal level, exposing Blake's vulnerabilities regarding this large girth, his ambiguous race (he is a blue eyed, white skinned man of African ancestry), and his sexuality.

Anthony Goicolea, like many younger artists, shares Blake's interest in the legacies of childhood. Goicolea's particular topic is the amorphous sensuality of adolescence, when one's body and its functions become the objects of obsessive interest. In Goicolea's photographs, groups of teenage boys hang out in basement dens or loiter by pools, trying out their new bodies by making obscene gestures, surreptiously kissing and spitting into one another's mouths, or turning a circle jerk into a contest to collect semen in a large jar. Goicolea, who looks younger than this 27 years, is the model for all the boys, posing in wigs and boys' clothes then assembling his self-portraits as groups in digital collages. The results are perfectly surreal, blending common memories of childhood with extreme acts of brattiness. Often cruel, the boys run amok in a suburban version of "Lord of the Flies," deep in the land of libido-driven id. While Goicolea's boys seem out-of-control with frantic

desire, Janine Gordon finds that desire can be examined with cool scrutiny - with hot results. A recent piece used the Internet's potential for real-time contact via video cameras and chat rooms. At the other end of Gordon's online relationship was a long-haired young man in Iceland. A virgin thousands of miles distant, he was desirable but unattainable, a problem exacerbated by his tendency to self-mutilation. Gordon documented their online encounters, preserving chats and still photos, then juxtaposed these with a narrative about two male friends who stopped by unannounced for some sex. Gordon has spent several years as one of the boys, photographing young men in the urban subcultures of hip-hop, punk, and skateboarding. In her low-contrast black-and-white photos, men are often erotically posed nude or simply preening their muscles and bravado. Gordon regards her photos as documents of her inclusion and involvement with men who are her friends rather than her subjects. As a group, these portraits are a blunt deconstruction of the masculine posturing. And social stereotypes, revealing the real men behind gangsta drag.

The follies of masculinity are plumbed by Andrew Bordwin and Adam Ames, who are teamed as Type A. The duo's short video clips often show the artists enacting manly (if somewhat ridiculous) feats. The artist may take on one another in wrestling or dodge ball, or engage in peurile contests to see who is fastest at leapfrogging cement pylons, climbing water towers, or pissing in adjacent toilet stalls. In Outstanding, Bordwin and Ames donned suits and headed to Wall Street, where they stood in the entrance of an office building for 45 minutes continuously shaking hands (this being New York, few passers-by took note). They also take on movie conventions, bringing Martin and Lewis schtick into the terrain of Scorcese and Tarantino.

They take turns rescuing one another from urban hazards -speeding cars, precipitous rooftops- or turn bad guy, as when Ames locked Bordwin in a car trunk. Like Goicolea and Gordon, Type A cracks the codes of masculine behaviour. Rob de Mar fuses reality and fantasy in his sculpture, situating tiny paradise islands atop spindly-looking metal poles usually a bit higher than the average viewer's head. Made from carved wood and found objects, both natural and manufactured, the scaled-down islands are typically customised with someone in mind. "Sophie" places a small cabin on a high hill, landscaped with tall pines from miniature train models. "Paradise II" and "Paradise III" bring the atmosphere in to these playful topographies, linking frothy clouds and several mountainous islands with thin umbilical lines. The use of miniatures is now common among young artists, but de Mar's frothy escapism is fairly unique. His confections inevitably draw the mind's eye to conjecture about perfect escapes. The interior space to which the mind retreats to daydream and space out is the landscape for Esther Partegàs's poetic work. A small figure sculpted in styrofoam stands isolated, his head dwarved by large headphones. Fine line drawing show people walking oblivious to one another, their heads covered by designer shopping bags. An aeroplane seat, sculpted to scale, is encumbered with all the attributes of a plugged-in, product conscious nomad: laptop computer, New York Times, shopping bags. Only the person is missing in this sculpture, entitled Homeless, and her absence is a heavy presence. From one Fleeting wish to Another, a projection of 162 slides of Partegàs's drawings, follows the slow trajectory of a bag floating against a cloudy sky. The effect is a mesmerising meditation on simple beauty (which is only by coincidence the same metaphor used at the conclusion of the film "American Beauty."). Among the most celebrated of emerging artists is Paul Pfeiffer, one of only six artists to appear in both "Greater New York" and the Whitney Biennial. Pfeiffer was also the first recipient of the Whitney's Bucksbaum Award, which grants $100,000 to promising American artists. Pfeiffer's reputation comes from his digitally enhanced video loops, but to focus on his nerdy acumen with special effects is to overlook his work in a variety of media, especially photography and sculpture, that stakes out new territory in art's traditional redoubts: the often dire contests of body, soul and mind. Heady stuff to which Pfeiffer adds heavy doses of mass culture. In an exhibition at The Project two years ago, Pfeiffer set a miniature window into a wall through which one could see Linda Blair's bedroom from "The Exorcist" rendered on doll-house scale. Complete with padded bedposts and sheets stained by green expectorate, the room was chillingly creepy. Never mind that the priests and possessed child were missing: this was the banal arena for an epic struggle of good and evil. One of Pfeiffer's contributions to the Biennial was a short video loop entitled Fragment of a Crucifixion (After Francis Bacon), in which a professional basketball player rocks back and forth screaming as the crowd behind him explodes with camera flashes. The image's power comes from its brevity. Pfeiffer isolates a few seconds of the player's action, removing any context beyond that provided by the title. The player's intensity is thus attributed with the agony of religious martyrs and Bacon's screaming popes.

The meta-physics of athletics is also the subject of a video at P.S.1. A spinning basketball occupies the perfect centre of the screen in John Bilb as the background whirls from one arena to another. The title's biblical reference to God's sacrifice of Jesus Christ - the most significant passage of the New Testament - is a ubiquitous feature courtside, inevitably appearing on placards held aloft by fans. In this digitally enhanced collage of images co-opted from dozens of televised games, the subject may be just a spinning ball, but it perfectly captures the awe of arena sports. It is easy to resent New York's dominance in the art world. And having read that its finest new art includes the fusion of art and basketball, and two grown men in a pissing contest, you may understandably question the propriety of the city's younger artists (as well as the tastes of your humble writer). But, I would argue, that lack of propriety is perhaps New York's greatest contribution to the art of the past 50 years. The city remains a depot of ideas, where artists are concentrated in greater numbers than anywhere else, vetting raw material with nary a thought for how future art historians will sort it all out. That may confound any consensus about art in America, but it is what is most engaging about New York art.

Grady T. Turner is a critic based in New York.