The Aspiration Factory

dal 7/6/2012 al 10/8/2012

Segnalato da

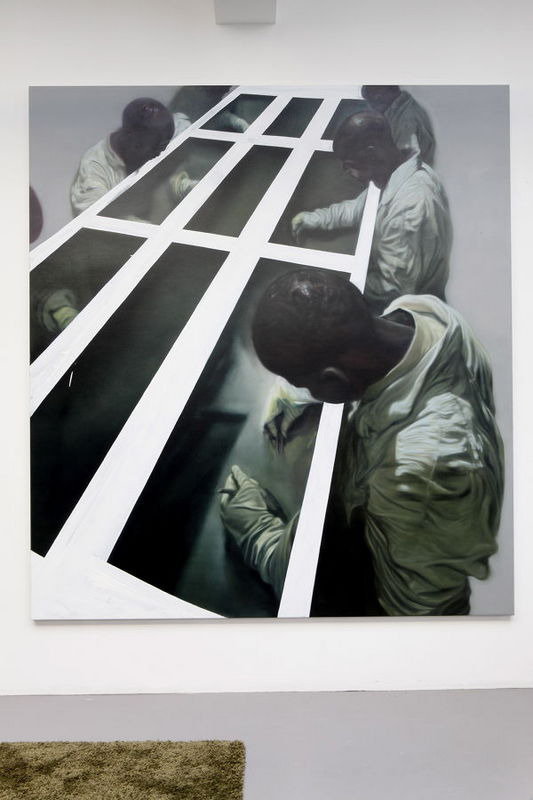

Stephan Balleux

Chris Barnes

Toby Christian

Kate Atkin

John Isaacs

Tom Crawford

Jean Katambayi Mukendi

Soren Dahlgaard

Laurent Jourquin

Charley Case

Marko Maetamm

JIMP

7/6/2012

The Aspiration Factory

Aeroplastics Contemporary, Bruxelles

The title of the group exhibition evokes a project still in-progress, an intensive investigation led by artists who aspire through their works to provide elements worthy of contemplation with respect to the field of art itself.

The title of the exhibition, Aspiration Factory, evokes a project still in-progress, an intensive investigation led by

artists who aspire through their works to provide elements worthy of contemplation with respect to the field of art

itself. With Stephan Balleux, these reflections concern painting as a medium: “You can see clearly that what

you are looking at is a painting, and thus artificial. But at the same time you also seem to be looking at

something that could be a photograph. The texture is flat, but portrays the texture of paint.”

The “Factory” is synonymous with experimentation, a central component in the technique of a painter, who

recognizes the frequent place occupied by chance, for example when he mixes colours directly on the canvas: “I

know what Iʼm doing and at the same time I donʼt know how I get there ultimately.” Similarly with Kate Atkin,

whose small and large drawings are made with existing images as a starting-point. Take the work Etude, for

instance. Here she takes Francis Baconʼs Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Cross: it has to do with

submitting oneself, at least in part, to the hazard of chance, and to see what flows from this encounter: “I see the

process of drawing as the generating of matter, and itʼs hard to know when to stop generating .”

This instability of the creative process, is seen by Chris Barnes as a foundation stone of the real (“the world we

attach to is unstable”); his sculptures of seemingly derisory appearance, closely akin to the ready-made, are first

and foremost a source of contentment for himself (“For me being an Artist is primarily about doing something that

makes me happy.”)

Along the same lines, the Appendices of Toby Christian, fragments in marble that seem to come from large

anthropomorphic sculptures, raises the question of the very status of a work of art: is that which is hidden of more

importance than that which is shown? Here, John Isaacs offers his own version spectacularly with Everything is

not enough – before the deluge ; a gigantic silver-plated hand with 6 fingers in which is inlaid a small TV screen ;

the imagination of the spectator is fiercely challenged to guess from which monument it has been taken. This

relationship with absence is also at the centre of the series Life Rooms, pieces of foam used by models for

support while posing for life (nude) studies, and which have retained the trace marks made by their feet.

Soren Dahlgaard or rather his alter-ego, the “Dough Warrior” whose body and have are dissimulated beneath a

mass of French breads (baguettes) revisits this artist/model dynamic in literally re-covering the body painting of

persons who pose for him, in the context of performances high in colour. With Tom Crawford, the thought

process turns political: his work studies the evolution of abandoned industrial sites that have gradually become

occupied by artists, then transformed for their gallery owners, and finally gentrified for their collectors.

Construction and habitat are at the heart of the series Bleeding Houses from Marko Mäetamm, who draws

inspiration from horror stories, setting in scene houses that are endowed with their own personalities (criminal, of

course); but by including buildings in his blood-soaked list such as the Atomium, the Yser tower, the Palace of

Justice in Brussels and the S.M.A.K. in Ghent, the artist lends a connotation that is clearly political as well as

cultural.

Born in the mining town of Lubumbashi, Jean Katambayi Mukendi underscores the importance of his origins in

the process that led him to become an artist, after training as an electrician (like his father), then as

mathematician: “As children, weʼd manipulate lots of metals. Weʼd make our own toys out of metal wire.” His

sculptures are elaborated starting from pieces of cardboard and scrap electrical appliances. Electricity, along

with its economic and sociologic impact (particularly in Africa where its production and management are often

quite problematical), is at the centre of his thinking. The subject is more current than ever after the Fukushima

disaster: energy produced by Man, or tapped from the sun?

With Charley Case, this questioning takes the form of a poetic image, with the solar star posed upon a network

of high-tension cables, in the mist of dawn. As for Dieu le Père from Laurent Jourquin, he has conclusively

opted for human technology: his eyes of LED light invite the viewer to mount in order to cross the otherwise

inaccessible gaze — but a beyond-the-tomb surprise awaits us at the summit! An off-beat humour with flavour of

morbidity as of JIMP's ; his drawings which aim to create a feeling of instability to the viewer are often inspired by

autobiographical experiences whose nature remains obscure.

P-Y Desaive

Image: Stephan Balleux, Spectrum, 2011-2012. Oil on canvas, 210 x 180cm

Opening: June, 7th 18-21

AEROPLASTICS contemporary

32 rue Blanche, 1060 Brussels, Belgium

Tuesday - Saturday: 14:00 - 18:00