Luc Andrie'

Laurence Bonvin

Gabriele Di Matteo

Walter Grab

Robert Heinecken

Jean Jacques Lebel

Jean Otth

Herve' Telemaque

3/6/2013

Cycle The Eternal Detour

Mamco, Geneve

2013 Summer Sequence. 8 monographic exhibitions on artists working from the second half of the twentieth century right up to the present day: Robert Heinecken, Jean-Jacques Lebel, Jean Otth, Herve' Telemaque, Luc Andrie', Gabriele Di Matteo, Laurence Bonvin and Walter Grab. Some of these already have an established place in art history, others are artists whose work the museum has been keeping track of for some time.

The summer 2013 sequence presents eight monographic exhibitions on artists working from the second half of the twentieth century right up to the present day. Some of these (Robert Heinecken, Jean-Jacques Lebel, Jean Otth and Hervé Télémaque) already have an established place in art history, and their research has paved the way for more recent art. Others (Luc Andrié and Gabriele Di Matteo) are artists whose work the museum has been keeping track of for some time and who have come back to show how their research has been progressing. Laurence Bonvin’s presence reflects Mamco’s ongoing interest in the regional photographic scene. Finally, the Swiss Surrealist petit-maître Walter Grab combines all three reasons for inclusion in the sequence.

---

Luc Andrié, Bolaño

Ten years after his exhibition Rien d’aimable (’Nothing nice’), and five years after presenting his strange portraits of the painter in his underpants (which he refuses to call self-portraits) at the Printemps de Toulouse, Luc Andrié is back at Mamco with a series of nineteen paintings entitled Bolaño. There is no longer anything uncomfortable about his subjects, his virtuosity is now accepted—and yet there is a problem. In the words of a famous art historian, ’There’s nothing there.’

The previous exhibition in the Cabinet des abstraits presented the photographic work of Pierre-Olivier Arnaud, in which the image had so little contrast that it seemed about to vanish into indeterminate greyness. In this sense, Luc Andrié provides a kind of continuity with his pale rectangles in unrewarding tones—grey-green with the odd hint of pink. The persevering viewer sees a face gradually emerging, but you have to look at it for a long time to make out a gaze that becomes a face, a closed face—and eventually realise that it is always the same one.

The face belongs to the Chilean poet and novelist Roberto Bolaño, who died ten years ago. Andrié became his travelling companion—an imaginary conversation partner. Moved by Bolaño’s sober yet shocking texts that tell without pathos of uprootedness, human misery and the depth of feeling—in short, the difficulty of being a poet—he wanted to prolong his encounter with the author. The nineteen paintings thus relate this silent consultation between painter and writer, the artist’s approach to this now mythical island in the archipelago of literature, in a Borgesian light. Each painting embolies the reading of the nineteen books by Bolaño that have been translated into French, from which each title selects a word that links the painter to the author.

But Andrié is not content just to pay tribute. His work as a painter also involves tackling the difficulties of his medium. What is the place—not to say legitimacy—of painted portraits in this day and age? How can you express what photography cannot, and how can you tackle the legacy of the portrait’s history? Such questions would suffice to wipe out the image, and hence—metaphorically speaking—they filter or obstruct its perception. And yet the face remains, like the painting. ’Disappearance isn’t my thing,’ says Andrié, ’it’s too romantic for me.’ This seems a paradoxical statement, given the care the painter takes to let the face emerge only in small stages, as though it had to pass through the hundred or so layers that lend his paintings pictorial depth. Yet he sees the persistence of the real and the face despite the filters—the screens that hide the picture or, in Bolaño’s writing, the violence that obliterates poetic activity.

The portraits of Bolaño are all derived from a single image found on the Internet. Painting from photography is a practice as old as Niépce and Daguerre’s invention itself, for painters have always considered that they can capture on the canvas something of the ’domain of the impalpable and the imaginary’ upon which photography should not be allowed to ’encroach’ (Baudelaire, The Salon of 1859). In Luc Andrié’s work, the shift from photographic to painted image adds an important time dimension. The instantaneous snapshot is drawn out into a laborious process of successive coatings, in which tones are nuanced through transparency. The result is a painted image, one that is very hard to photograph and is only very gradually revealed to our eyes. Thus, in contrast to the immediacy of the photograph—from snapshot to viewing—the experience of painting is closer to that of literature, in which our gaze advances and progresses step by step, entering a world in which what we see must be enhanced by what we imagine.

---

Laurence Bonvin, Passing

Since the beginning of her career in 1993, Laurence Bonvin has made her mark in landscape photography, and specifically the photography of peripheral urban landscapes, and landscapes she walks through, from Berlin to Johannesburg, from Geneva to Istanbul.

Bonvin approaches these cities through a process of exploration and research, without ever knowing where it will lead. Sometimes her attention is caught by a piece of urban design that has been dropped in the midst of the landscape—an example being ’gated communities’, which captured her interest because they imported an American suburban model into a quite different cultural and economic setting. Elsewhere she looks at how people appropriate—or reappropriate—a space marked by history. How do you photograph the invisible trace of a buried past that is still very present in people’s minds?

Laurence Bonvin generally prefers the periphery—disadvantaged areas where change can be more dynamic—to the centre. But the distinction is not necessarily a geographical one. In Johannesburg, since the end of apartheid, the city’s economic centre has shifted to the well-heeled northern suburbs, while the abandoned city centre has crumbled into an assortment of sleazy neighbour-hoods. On her first visit to South Africa in 2009, Bonvin photographed the townships—the districts set aside for black people under apartheid, now swiftly developing, but with stark contrasts between promise and reality—or prefabricated walls and areas of wasteland. On returning in 2012 she embarked on a new project based on the following simple process: she stood on a street corner in the downgraded city centre for an hour or so and took pictures of the passers-by.

Although her work is usually associated with documentary photography—despite its strong propensity to trigger the viewer’s imagination—Bonvin here adopts the codes of street photography, focused on human beings. But however complex the reality recorded in her work, this is not a gallery of characters; for the recurring, underlying character in the series is South African society itself, with its outpouring of energy into extreme, normalised violence, as well as into hopes of reconciliation and reconstruction. The photographer captures the chaotic staging of street-corner theatre, where all the actors seem to be acting just for themselves. Their bodies brush together and sidestep in a ballet of intersecting but separate pathways. The body is an issue for Bonvin personally: a white woman standing alone and motionless in a dangerous neighbourhood, taking pictures in the middle of the street. The standard vocabulary of photographic ’stalking’, of hunter and prey, is turned on its head. The resulting pictures suggest the awkwardness of this phys- ical confrontation. Contact seems to be ruled out. The walking figures turn away, lower their eyes, ignore the photographer, stare at her dully—and move on. Bonvin’s constant use of the selfsame angle, in which the same person sometimes turns up more than once, imbues the series with a sense of time and narrative potential. What emerges is an ambivalent take on the status of the pictures and the many meanings of ’passing’.

Bonvin’s work is exhibited here in collaboration with the Geneva-based photographic event 50 JPG.

---

Gabriele Di Matteo, China made in Italy

Originally from the Naples area but now based in Milan, the painter Gabriele Di Matteo has exhibited at Mamco many times, and one of his small paintings is on permanent display on a staircase at the museum. The exhibition China made in Italy is a new exploration of the production processes he regularly uses, often involving repetition, delegation and a choice of motifs that are very often deceptive.

Produced in 2009, the series of paintings shown at Mamco this summer consists of some sixty canvases that may either be classically hung on a wall or else left lying on the ground, resting on a picture rail. Visitors to the exhibition thus get the feeling they are in the artist’s studio, or rather in a factory full of pictures that are stored there until they can be sent elsewhere—very much in keeping with the spirit of Gabriele Di Matteo’s work, for he is basically an image maker. In producing these paintings he has once again turned to a Neapolitan painter who specialises in certain kinds of motif (such as flowers or the sea) and then processes them systematically and mass-produces them for the general public, especially tourists. In short, Di Matteo has had the paintings made by a practically unknown painter who normally turns out entire series of images devoid of serious artistic pretentions.

These are genuinely hand-painted each time, in large numbers. In terms of their execution, they thus reflect a view of the artist that has been fully developed by Modernists and such present-day artists as Warhol, Manzoni, Angela Bulloch, as an incarnation or instigator of a painting machine, even if their aesthetics ignore Modernism and its history. As their titles make clear, they are reproductions of paintings by contemporary Chinese painters, paintings that can be seen as photographs in art catalogues or journals (the word ‘after’ in the titles recalls its use by Sherrie Levine to describe her own copies of major works of Western Modernism). A total of fifteen artists have been picked for this series, based on a selection of four or five specimens of their work, according to a specific criterion: they are the Chinese painters who are currently most successful on the art market (such as Yue Minjun, Shi Xinning and Zhao Bo). Rather than an aesthetic approach, this is a sober assessment of commercial value as a driving factor in the production of images. The often large paintings are all black, white or grey, unlike almost all the originals, which are mainly in garish colours. This allows Di Matteo to give the series a visual uniformity beyond the pronounced difference in the motifs, and to appropriate the originals (this grey-tinted world recalls The Blind Man, a series of paintings by the artist that are part of the Mamco collection). The copies may include slight, even tiny variations, for the issue here is the possibility of perfect reproduction, of absolute repetition, on the understanding that the difference between the original and the copy of it is unbridgeable. And if every painting is unique, this is because the hand that paints, regardless of its skill, is always a hand that invents, and produces variations. There is a great deal of freedom and irony in China made in Italy: whereas old Europe is in the throes of an economic crisis that is partly due to the relocation of its industrial production to China, Di Matteo has relocated the production of Chinese painting to Naples; whereas the originals are made by the new stars of the globalised art market, the copies are the work of an almost unknown image-maker from a local market; whereas the originals often celebrate a joyful, charming, almost carefree use of colour, their Western version is visually attenuated, and incomparably more serious. And whereas Mamco usually collects what is supposedly art, great art, Gabriele Di Matteo shows us that this category is as questionable as the strident—and typically Western—celebration of originality.

---

Walter Grab, Du peu de réalité

Mamco has taken an interest in the Swiss Surrealist petit-maître Walter Grab for various reasons. The ramifications of Surrealism have deeply penetrated the museum’s subconscious, as repeatedly displayed on the first floor of the building, for example in Gérald Minkoff’s Un portrait (‘A portrait’, winter 2010-2011) and above all in La vie dans les plis (‘Life in the folds’, summer 2012). As for Walter Grab, he is an unusual local example of the persistence of the Surrealist style and the flexibility of its themes.

Today, Walter Grab is practically unknown. This self- taught painter became part of Switzerland’s post-war art scene, and in 1950 he helped found the Phoenix group, which brought together Swiss, Austrian and German Surrealists such as Kurt Seligmann, Otto Tschumi, Ernst Fuchs and even Arnulf Rainer. During the 1950s, Grab took part in several exhibitions of international Surrealism, in Copenhagen, Munich, Berlin and Zurich. His works were included in Swiss museum collections in Zurich and Aarau, and in 1965, together with Meret Oppenheim, he even represented Switzerland at the São Paulo Biennial. But there—after, despite regular exhibitions at his gallery in Zurich, he lapsed into an oblivion from which Mamco is proud to rescue him—for although he remained on the sidelines of developments in the contemporary art of his time, Grab was a fascinating artist who over the decades evolved an ever more personal and controlled style until he eventually became a veritable petit-maître. So it is only logi- cal that he should be the next artist after Julius Kaesdorf to be exhibited in the Stanza.

His paintings incorporate various features from the Surrealist pictorial vocabulary. The most obvious of these are the pallid backgrounds, from glaucous blue or turquoise to pale yellow. Mixed in with this are biomorphic forms, figures reminiscent of Picabia, as well as a geometricism inherited from Kandinsky and texts, mathematical formulae and diagrams that recall scientific, even esoteric illustrations. The resulting images veer between Surrealistic landscapes and Modernist abstraction, coldly dreamlike images and science fiction. And yet, despite the growing idiosyncrasy of his work, Grab remained in dialogue with the Surrealists right up to the end of his life—as witness his Waldsymphonie (‘Forest symphony’, 1985) with its commentary on Max Ernst’s Forest (1927) and Forest and sun (1931), organised with the precision of an electronic circuit board.

---

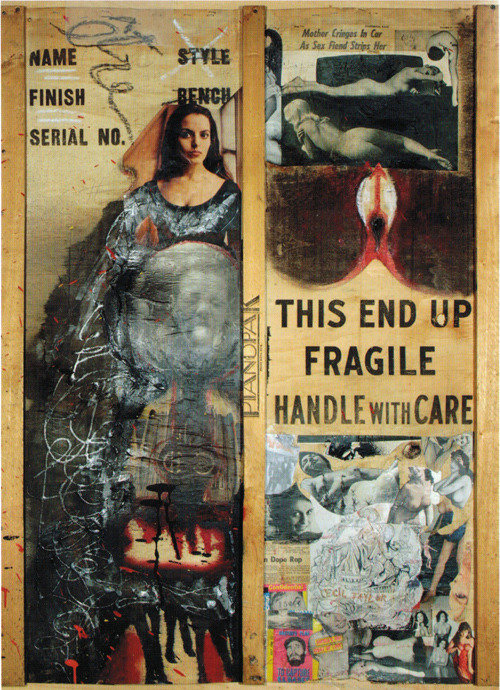

Robert Heinecken, Le Paraphotographe

How do you present a photographic work amid a profusion of images? What resources do you use? And what are you trying to say? These are questions Robert Heinecken began asking himself in the early 1960s. As an artist he set out to explore these issues over the next four decades, and as a professor at the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA) he awoke generations of students to their existence. Yet, ironically, his position in the field of photography relegated him to the sidelines of institutional fame and commercial success, even though the worthwhile answers he sought early on made him highly influential among artists themselves.

Even today, in an age of Babel-like image banks, there is something exhilarating about the work of an artist who blended his vocabularies, for instance by corrupting doc- umentary photography with images from advertising or pornography. But the humour and charm, however wry, that recur throughout his work should not blind us to his serious approach to theoretical issues (especially on the use of the photographic medium) and social ones alike. Heinecken used the term ’paraphotographer’ to describe his ambiguous relationship with his medium. On the one hand, he almost always used existing images that he compiled or arranged to create his own works, which might lead some to consider that he was not a photographer in the strict sense of the term; yet he was a true virtuoso in printing and trans- fer techniques, understanding their connotations and using the various methods as styles in their own right.

In an age of widespread protest, Robert Heinecken used guerrilla techniques to disseminate his work, altering magazines which were then redistributed in kiosks or salons. The subversive ability of these altered magazines was enhanced by the surprise effect. On 28 November 1969, the cover of Time Magazine showed a strange photograph of an epoxy-resin portrait of Raquel Welch, by the sculp- tor Frank Gallo. Heinecken enhanced the ambiguity by overprinting on the inner pages erotic photographs that distorted the meaning of the articles and focused on the depiction of women as mere objects. Far more scathing and merciless was Related to periodical #5, in which a picture of a smiling woman soldier brandishing two severed heads was superimposed on advertisements for anti-baldness creams, or on an article about birth control from women’s point of view. Heinecken worked in series. For instance, the various Lessons in Posing Subjects brought together pictures rephotographed as Polaroids and arranged according to posture. He used ironic captions to mock the standardising impact of the mass media, especially television, which he saw as a place of involuntary surrealism. Several of his series dealt with this issue, mixing up presenters’ faces or highlighting the absurdity of the televised spectacle.

’I make something to see what it looks like,’ said Heinecken, ’and to see if it looks like anything else.’ Given the diversity of the methods he tried out, and the issues he tackled, his work was unlike any other—diagnosing the ills of the society he was part of, and tracing the history of artistic research in the closing decades of the twentieth century.

---

Jean-Jacques Lebel, Soulèvements II, 1951-2013

Soulèvements II (’Risings II’, 1951-2013) is not so much a retrospective on the work of Jean-Jacques Lebel as a non-exhaustive overview of more than fifty years of creation reflecting the various directions the artist has taken (collages, happenings, drawings, paintings, installations, assemblages and so on) through a process of exploration of the limits of art and the institutions that exhibit it. The title echoes the retrospective of the artist’s work at La Maison rouge in Paris in autumn 2009, Soulèvements (’Risings’).

Occupying the whole of the second floor at Mamco, the exhibition shows Jean-Jacques Lebel’s first paintings, produced in 1951. This process was marked early on by a wish to break away from the standard framework of art and open up the plastic world to new, radical explorations. Thus, in Venice in 1960, Lebel produced the first European happening L’Enterrement de la Chose (’Burial of the Thing’), the ’Thing’ being a Jean Tinguely sculpture on its way to its final resting place in a procession through the city and along its canals after the work had been killed (the execution of art for art’s sake). Up to 1968 Lebel was to produce numerous happenings around the world (more than seventy of them), and these would be the main facet of his work. But thereafter he decided to abandon happenings, considering them too common in the art world to still be relevant. Soulèvements IIdisplays on a wall (in A3 and A4 size) almost a hundred photographs of these happenings—transient, collective moments that are never lost as such, and seen here through the archives signed and titled by the artist. The images reveal the predominant position of the body and the Dionysian expression of its urges in an artistic practice that the art market cannot cope with. Another stage in this process, Les Avatars de Vénus (’Avatars of Venus’, 2003), is in Lebel’s view one of the key items in the exhibition—images of womanhood projected on four screens that can be seen from both sides within a cube. ’Viewers can walk through it in their own way, while a constantly changing random collage unwinds. What we are seeing is a morphogenesis of Venusian beauty. Each clash of images produces new ’morphs... this isn’t cinema, but painting in motion, “in the process of becoming”’, the artist confides. Here again we see a wish to move beyond artistic categories, turning the viewer into the walker through an installation that is also a walk through the history of the depiction of desire and the female body. Among the most striking works in this vast presentation, the Grand tableau antifasciste collectif (’Great collective antifascist painting’, 1961) by Erró, Camilla Adami, Peter Saul and Jean-Jacques Lebel, which at the time was displayed throughout Europe, illustrates the artist’s political commitment and the collective dimension of his world. Another prominent moment in the process is the maze of images created to mark Soulèvements II: thirty-eight pictures of torture taken from the Internet, printed in colour on strips that one of the sides of the maze, whereas on the walls we can see in black and white the results of the disasters caused by warfare, without the victims being present. Lebel believes art is there to express what is repressed and to display the unbearable—even if that means forcing us out of our moral and intellectual comfort zones.

Deleuze and Guattari’s ideas and procedures regarding the rhizome are clearly at the heart of Lebel’s work : they imply that artistic activity produces proliferating links, juxtapositions, non-hierarchical relationships between beings and things—friendships—which expand everyone’s living space and open up new sides of the subjectivation process, which must constantly be explored. And hence Lebel’s work and life are also marked by companionships (including with André Breton, Marcel Duchamp, Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, Allan Kaprow and Allen Ginsberg) which are an integral part of his artistic world and a way of seeing the artist as a purveyor of forms, ideas, and intensities, an activator of encounters. And thus Soulèvements II, and their rebellious

identities, are a set of juxtapositions and links.

---

Jean Otth, Rêverie Zénonienne, 1972-2013

A pioneer of video art, Jean Otth began working in Switzerland in the early 1970s after completing his art history and philosophy studies in Lausanne (he subsequently spent some of his time teaching). His Rêverie zénonienne (‘Zenonian Reverie’, 1968-2013) – a phrase taken from Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s work L’Œil et l’Esprit (‘Eye and Mind’)—is an exhibition of his work with a retrospective component, although it focuses on the last ten years of his work, which is now shown at Mamco for the first time.

‘Having always felt that any image is obscene in the etymological sense of the word, and that the only way to rescue it is to obliterate and blunt it, I’ve rejected it not in order to destroy it but to help it exist....’, says Jean Otth, speaking of his work on images. The ‘obscenity’ he refers to (the Latin word obscenus means ‘ill-omened’) is the fore- boding he believes is contained in any perfectly perceptible image. So what is seen must be injured, damaged, made more complex in order to rescue it—and hence the possibility of looking—and preserve the future. To reveal, we must disguise. Thus many of the devices to be seen in Rêverie zénonienne—the title of the exhibition, but also the generic title of a series of works created since 2001—are based on processes of obliteration of the centre of the projection, the centre of attention: for instance, by painting a black rectangle on a wall and then projecting a video based on digitally processed film images around it rather than directly on it, Otth combines the fixity and the instability of an image that is both pictorial and videographic and hence captures the viewer’s gaze and requires it to view the work from a kind of central—and active—black hole.

Revolving around the latter is thus what the artist calls the parergon, which, despite being outside the work (the literal meaning of the Greek term), nonetheless affects its constitution and identity. ‘My purpose is to add a genuine movement to the movement the painting displays in its immobility and its simulation—a feature I see as an additional colour on the painter’s palette.’ This work thus includes a pictorial dimension (Jean Otth started out as a painter) in the exploration of video as a medium, as a subject, analogue in the 1970s and digital today. Hence the works are not narrative and are not based on the creation of fiction (it is the medium as such that is summoned up through its very nature, even more than its ability to represent), as well as the fact that they take account of the space of the wall. Seeing or making paintings with, or on the basis of, video can be seen quite explicitly in a work from 1972, Hommage à Mondrian (‘Tribute to Mondrian’), in which a painting by Mondrian is filmed face-on and in which disruptions in the image—the work is part of a series called Vidéo perturbations (‘Video disruptions’) in which the visual image is technically messed up—are shown as such (ultimately this is a history of painting after, and according to, video which makes the technical depth of the instrument truly palpable).

Other works in the exhibition refer directly to painting such as the mirror paintings of the late 1960s or the murals or paintings under glass of the 1980s. The Rêverie zénonienne series, Otth’s most recent work, is fully represented here. It suggests a meditation on time through painting rather than an exploration of movement, and includes works such as Héraclite au Parc Bourget (‘Heraclitus in Parc Bourget’) which deal with photon flux, with a constant sensory and formal rigour—a way to keep on questioning the plastic and philosophical issues in the often conflicting relationships between representation and non-representation, painting and video. Finally, as Otth himself says, ‘the exhibition tells of the illusions of meaning and the illusion of the senses, in Pessoa’s words:

The main thing is knowing how to see

Knowing how to see without thinking

Knowing how to see when one sees

And not thinking when one sees

Nor seeing when one’s thinking.’

This goes to show that the purpose of this work is to achieve a full, entire gaze, nothing but a gaze, a vision as such, through a medium whose potential it puts into practice.

---

Hervé Télémaque, Ciels de lits, 1959-1970

In 1961, Hervé Télémaque arrived in Paris after four years spent studying in New York. He then met André Breton and made contact with the Surrealists, though he never actually took an active part in the movement. Haiti (his birthplace), New York and Paris were three cultural worlds on which he would draw in developing his own vocabulary as a painter. The exhibition at Mamco shows a decade of work in which Télémaque laid the foundations for his later artistic output.

In the United States, Hervé Télémaque studied at the Art Students League of New York, where he saw an Abstract Expressionism that was too triumphant not to decline soon; but he refused to follow the path of the stirring gesture. While in New York he also saw American Pop Art in its infancy; it interested him from a stylistic point of view, and he shared its fascination with the products of mass culture. Yet his ‘pop’ references differed from those of the artists who truly belonged to the movement, tending instead to come from the counter-culture and ideologies of protest. The comic books that would nourish his formal repertoire were Mad and the work of Harvey Kurtzman rather than the All-American Men of War that so inspired Roy Lichtenstein—for in late 1950s America Télémaque was of course part of a minority and suffered from prejudice which his family background had hardly prepared him for, and which put him in mind of his own forefathers’ disheartening past. This no doubt played a part in his decision to quit the States and move to France.

In Paris he came across the Surrealists, and accordingly his canvases reflect a fondness for strange associations which may seem random but in fact function as semantic links. Each object ‘contaminates’ the meanings of the ones around it, and their arrangement is not a logical sequence but an allusive, collusive set of forms bound together by tenuous, uncertain and yet inextricable threads.

In 1964, Hervé Télémaque took part in Mythologies quotidiennes (‘Everyday mythologies’) at the Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris and then, the following fall, in La figurationnarrativedans l’art contemporain (‘Narrative figuration in contemporary art’); both exhibitions were organised by the critic Gérald Gassiot-Talabot. The painter thus became part of a movement that rejected both abstraction and New Realism, and sought to respond to American Pop Art by ‘displaying a creative subjectivism’. Indeed, his painting is not just subjective but idiosyncratic, as if he were deliberately trying to confuse the viewer. The forms in his compositions float against plain, compartmentalised backgrounds, often in very vivid colours and sometimes soiled. The figures grimace and the objects are disconcerting, even though their links to painting, the artist’s previous history or social issues can be imagined: pieces of underwear, the white canes used by the blind, logos, weapons and pointing fingers all serve to poke fun at stereotypes, or as puzzles that prevent one-sided interpretations. Télémaque has retained his linguistic roots, with a thorough mastery of French—his uncle was the poet Carl Brouard—and just a hint of Haitian Creole. So language, too, is part of his attempts to sow uncertainty: in his poetic titles and the inscriptions on his canvases, he uses words like materials rendered down to yield semantic oddities that give his world an unusual status amid the linguistic uniformity of the art scene.

If his figuration is narrative, the narrative is ambivalent, fragmented and dialectic, with its share of mockery, zaniness, irony and secrecy. This is painting that evades discourse, as it evades categorisation.

---

Press: Sophie Eigenmann

Responsable des relations avec la presse

s.eigenmann@mamco.ch

Press conference, Tuesday 4 June at 11 a.m.; show opening starting at 18:00 on the ground floor of the Batiment d'art contemporain.

Mamco | Musée d¹art moderne et contemporain

10 rue des Vieux-Grenadiers Genève

Open Thuesday through Friday from noon to 6 p.m., the first Wednesday of the month until 9 p.m., and Saturday and Sunday from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Closed Mondays as well as Friday 6 April, Sunday 27 and Monday 28 May 2012.

Regular admission CHF 8, reduced admission CHF 6, group admission CHF 4