La Noche espanola

dal 20/12/2007 al 23/3/2008

Segnalato da

20/12/2007

La Noche espanola

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid

Flamenco, avanguardia e cultura popolare 1865-1936. L'esposizione riunisce per la prima volta una selezione di opere che evidenziano l'importanza del flamenco nella cultura visiva e in particolar modo le sue relazioni con la modernita' e le avanguardie artistiche. In mostra 450 opere tra pittura, scultura, disegni decorativi, costumi per la danza e il teatro, fotografie, publicazioni e documenti di autori europei e americani, oltre a piu' di 40 proiezioni video. Curata da Patricia Molins e Pedro G. Romero.

Curated by Patricia Molins and Pedro G. Romero.

Flamenco (conceived as modern popular culture) and the artistic avant-garde appeared in the late 19th century. In 1865 Édouard Manet travelled to Spain to see the paintings of the Spanish masters for himself and the cantaor Silverio Franconetti returned to Seville to lay the foundations for what would be flamenco song. At that time the railway linking Andalusia to Madrid and Paris had just been completed and the movements that would lead to the First Republic were gaining momentum. The flamenco dancers were self-taught and worked at private parties or in the café cantante, a Spanish form of cabaret.

Around 1900. “Black” Spain

The exhibition begins with a portrait by William Merrit Chase of the ballerina Carmencita, who performed in New York at the end of the 19th century. She was the first woman ever to be filmed in the history of cinema (by Thomas Edison). Before Chase, Édouard Manet had not only used Spanish motifs in his work but, as a result of this, a new way of painting that followed on from Velázquez and paved the way for Impressionism. The Bécquer brothers were the first to take up the theme of Spanish dance, focusing not only on the realism of anthropological representation but on the popular character of dance, which made it an ideal medium for social and political criticism. Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer’s self-portrait in which female figures materialize in the smoke of his cigar gives an idea of how dance opened a window onto a world of fantasy and leisure - “another world”. Nevertheless, the caricatures of SEM (the pseudonym of a group to which the Bécquer brothers belonged) revealed how that “other” world could speak of reality.

The publication of España negra, a travel book by E. Verhaeren and Darío de Regoyos, offered a grim, pessimistic view of Spain that lasted well into the 20th century. Regoyos, Solana and Nonell were instrumental to defining that image along with other painters traditionally considered luminists like Anglada Camarasa and Sorolla. Pastora Imperio was the bailaora of this tragic Spain, which could be followed on stage at the popular fairs and town cafés. The world of the gypsies, those other Spaniards par excellence, forms part of these dark images.

1910-20. Cubism and the Ballets Russes

With the spread of Cubism and the arrival in the Iberian peninsula of artists like Gleizes, Picabia and the Delaunays, who were fleeing the First World War, Spanish dance became a model of abstract and decorative rhythm. Various artists -including Picasso, Severini and Lipchitz- used the image of the female dancer to deconstruct form, moving from figurativeness to stylization or abstraction. The guitar, with contours often identified with the female body, was also a motif in numerous compositions. Local Madrid scenes became a successful genre, encompassing advertising and touristic points of view, the study of folklore, and the reflection on identity. It was also a time of excess and parties and therefore the flamenco motif appears in many of them. Fancy dress and tranvestism often bore Spanish characteristics.

The Ballets Russes also arrived in Spain at this time and with them Picasso and Goncharova as set designers. Some flamenco dancers identified with their Russian counterparts, understanding that both Russian and Spanish dance lay in an intermediate zone between the popular and the classical, between east and west. The modus operandi of the Russians encouraged a few of the Spaniards then working in Paris -like La Argentina (Antonia Mercé) or Vicente Escudero- to found companies and, in cooperation with artists (Néstor, Sáenz de Tejada..) and musicians (Falla, Albéniz…), produce stage shows on a grand scale intended for large international theatres, not only for local theatres or cafés cantantes.

The Republic. “Eternal” Spain, and the españolada

Here the key figures were Picabia, Miró and Man Ray, who generated a certain radicalism that coincided with the consolidation of stereotypes in avant-garde art and flamenco. Fully aware of its identity, flamenco was torn between aesthetic purism and and commercial cliché. The 1927 Generation explored the modern ludic virtues of fairs and festivals but also viewed “eternal” Spain with a critical eye. Both appear in images by Dalí, Lorca and Giménez Caballero. Cinema and cliché championed by advertising influenced painting as images by Romero de Torres and Martín Durban confirm. Spanish cinema was concerned about regailing its public with local affairs and depicted “the Spanish” only superficially - bulls, mantillas, gentlemen of leisure, Andalusian charm, dishonoured women struggling against the odds- but also related these to suburban or rural life, contrasting the world of the gentlemen of leisure with that of the poor. The figure of the bailaora Carmen Amaya, wearing trousers and heel-tapping furiously, sums up that paradoxically new image of eternal, dramatic, battling Spain.

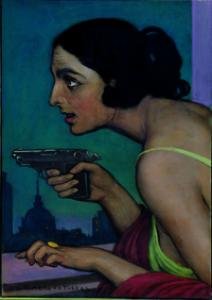

Image: Julio Romero Torres

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

Santa Isabel, 52 Madrid

Time: Monday to Saturday from 10:00 to 21:00 h

Sunday from 10:00 to 14:30 h

Closed on Tuesday