Laszlo Moholy-Nagy

dal 6/10/2009 al 6/2/2010

Segnalato da

6/10/2009

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy

Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt

Comprising roughly 170 works in the mediums of painting, photography and photogram, sculpture, and film as well as stage set design and typography from all phases of his career, the retrospective will examine the complex picture of Moholy-Nagy's oeuvre in order to present the range of his creative output to the public for the first time since the last major exhibition of his work in Kassel in 1991. Never having been built before 2009, the artist's spatial design 'The Room of Our Time', which brings together many of his theories, will be realized in the context of the exhibition.

Curated by Ingrid Pfeiffer

The Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946) became known in Germany through his

seminal work as a teacher at the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau (1923–1928). His

pioneering theories on art as a testing ground for new forms of expression and their application to

all spheres of modern life are still of influence today. Presenting about 170 works – paintings,

photographs and photograms, sculptures and films, as well as stage set designs and typographical

projects – the retrospective encompasses all phases of his oeuvre.

On the occasion of the ninetieth

anniversary of the foundation of the Bauhaus, it offers a survey of the enormous range of Moholy-

Nagy’s creative output to the public for the first time since the last major exhibition of his work in

Kassel in 1991. Never having been built before 2009, the artist’s spatial design The Room of Our

Time, which brings together many of his theories, will be realized in the context of the exhibition.

The “László Moholy-Nagy Retrospective” is sponsored by the Hessische Kulturstiftung and

receives additional support from the Fazit-Stiftung.

No other teacher at the Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau, nor nearly any other artist of the 1920s

in Germany, an epoch rich in utopian designs, developed such a wide range of ideas and

activities as László Moholy-Nagy, who was born in Bácsborsód in Southern Hungary in 1895. His

oeuvre bears evidence to the fact that he considered painting and film, photography and

sculpture, stage set design, drawing, and the photogram to be of equal importance. He

continually fell back upon these means of expression, using them alternately, varying them, and

taking them up again as parts of a universal concept whose pivot was the alert, curious, and

unrestrained experimental mind of the “multimedia” artist himself.

Long before people began to

talk about “media design” and professional “marketing,” Moholy-Nagy worked in these fields, too

– as a guiding intellectual force in terms of new technical, design and educational instruments.

“All design areas of life are closely interlinked,” he wrote about 1925 and was, despite his motto

insisting on “the unity of art and technology,” no uncritical admirer of the machine age, but rather

a humanist who was open-minded about technology. His basic attitude as an artist, which

exemplifies the idealistic and utopian thinking of an entire era, may be summed up as aimed at

improving the quality of life, avoiding specialization, and employing science and technology for

the enrichment and heightening of human experience.

After having graduated from high school, Moholy-Nagy began to study law in Budapest in 1913,

but was drafted in 1915. During the war, he made his first drawings on forces mail cards and

began dedicating himself exclusively to art after having been discharged from the army in 1918.

Moholy-Nagy moved to Vienna in 1919 and to Berlin the following year, kept in close contact with

Kurt Schwitters, Raul Hausmann, Theo van Doesburg, and El Lissitzky, and immersed himself in

Merzkunst, De Stijl, and Constructivism. He achieved successes as an artist with his solo

presentation in the Berlin gallery “Der Sturm” (1922), for example. In spring 1923, he was offered

the post of a Bauhaus master in Weimar by Walter Gropius.

Taking responsibility for the

preliminary course and the metal workshop, he decisively informed the Constructivist and social

reorientation of the Bauhaus. Interlinking art, life, and technology and underscoring the visual and

the material aspects in design were key issues of his work and resulted in a modern, technology-

oriented language of forms. His didactic approaches as a Bauhaus teacher still present

themselves as up-to-date as his work as an artist. For him, education had to be primarily aimed at

bringing up people to become artistically political and creative beings: “Every healthy person has

a deep capacity for bringing to development the creative energies found in his/her nature ... and

can give form to his/her emotions in any material (which is not synonymous with ‘art’),” he wrote

in 1929.

In spite of his manifold activities and inventions in the sphere of so-called applied art, Moholy-

Nagy by no means advocated abolishing free art. Before, during, and long after his years at the

Bauhaus, he produced numerous paintings, drawings, collages, woodcuts, and linocuts, as well

as photographs and films as autonomous works of art. Like his design solutions, his works in the

classical arts, in painting and sculpture, also reveal his aesthetically and conceptually radical

approach. His Telephone Pictures, whose execution he controlled by telephone, exemplify this

dimension: using a special graph paper and a color chart, he worked out the composition and

colors of the pictures and had them realized according to his telephonic instructions by technical

assistants.

He also pursued new paths with his famous Light-Space Modulator of 1930,

conceiving his gesamtkunstwerk composed of color, light, and movement as an “apparatus for

the demonstration of the effects of light and movement.” It was equally new territory he

conquered in the fields of photography and film: considering his cameraless photography, his

photograms, and his abstract films such as Light Play Black, White, Gray (1930), Moholy-Nagy

must still be regarded as one of the most important twentieth-century photographers and key

figures for today’s media theories.

Thanks to his experiments with photography and the photogram, László Moholy-Nagy was one of

the first typographers of the 1920s to recognize the new possibilities offered by the combination of

typeface, surface design, and pictorial signs with recent photographic techniques. As a Bauhaus

teacher for typography, he designed almost all of the 14 Bauhaus books published between 1925

and 1929 and – besides co-editing them with Walter Gropius – took care of the entire presentation

of the books’ contents and the organization of their production. With its dynamic cycles and bars

and concentration on a few, clear colors, their design resembled the Constructivist artists’

paintings and drawings. While Moholy-Nagy’s early typographic works are frequently still

characterized by hand-drawn typefaces, he later strove for a “mechanized graphic design” also

suited for commercial advertising through their systematization and standardization.

After he had

left the Bauhaus in 1928, he founded his own office in Berlin, where he, among other things,

developed advertising solutions for Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s designs for the Jena Glassworks. Faced

with the Nazis’ seizure of power, Moholy-Nagy emigrated to the United States via Amsterdam and

Great Britain and founded the New Bauhaus in Chicago in 1937 and, after it had been closed, the

Chicago School (and later Institute) of Design in 1939, where he continued to champion an

integration of art, science, and technology. László Moholy-Nagy died of leukemia in Chicago on

24 November 1946.

The exhibition at the Schirn also presents The Room of Our Time, which offers a concise summary

of Moholy-Nagy’s work. The sketches for this environment, which assembles many of his theories,

date back as far as 1930. Not having been built before 2009, The Room of Our Time is now

realized in the Schirn on the occasion of the Bauhaus anniversary 2009.

CATALOG: László Moholy-Nagy. Edited by Ingrid Pfeiffer and Max Hollein. With a preface by Max

Hollein and texts by Ulrike Gärtner, Kai-Uwe Hemken, Gerald Köhler, Herbert Molderings, Ingrid

Pfeiffer, and Joyce Tsai. German and English editions, 192 pages and 220 illustrations each,

Prestel Verlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-7913-5002-8 (English), ISBN 978-3-7913-5001-1

(German), 29.80 € (Schirn) / 49.95 € (trade edition).

PRESS OFFICE: Dorothea Apovnik (head of press and public relations),

Tanja Wentzlaff-Eggebert (press officer), Philipp Dieterich,

phone: (+49-69) 29 98 82-118, fax: (+49-69) 29 98 82-240,

e-mail:

presse@schirn.de

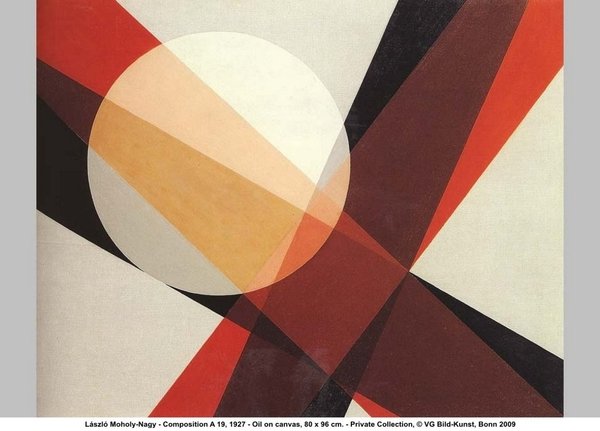

Image: László Moholy-Nagy, Composition A 19, 1927

Press preview: Wednesday, 7 October 2009, 11:00 a.m.

Schirn Kunsthalle

Romerberg - Frankfurt

Opening hours: Tue, Fri - Sun 10 PM - 7 AM

Wed and Thu 10 AM - 10 PM

ADMISSION: 8 €, reduced 6 €, family ticket 16 €; combination ticket also admitting to the exhibition “Art for the

Millions. 100 Sculptures from the Mao Era” 13 €, reduced 9 €.

Free admission for children under

8 years of age.

GENERAL GUIDED TOURS: Tue 5 p.m., Wed 7 p.m., Thur 8 p.m., Fri 11 a.m.,

Sat 3 p.m., Sun 5 p.m.