L'edicola digitale delle riviste italiane di arte e cultura contemporanea

Virus (1994 - 1998) Anno Numero 14 ott-nov '98

Renée Cox

Interview by Cristinerose Parravicini

Mutation

LOIS KEIDAN

intervista di Franko B

n. 2 febbraio '98

Fear and loathing in Las Vegas di Terry Gilliam

Gianni Canova

n. 4 sett-ott-nov

Jenny Holzer - Interview

by Florence Lynch

n. 10 gennaio 1997

Incontro con Lea Vergine

FAM

n. 10 gennaio 1997

Movimento lento

di Renata Molho

n. 14 ott-nov '98

Teddy Bears Company

Intervista di Antonio Caronia

n. 14 ott-nov '98

Renée Cox is an artist who lives and works in New York City. She has received two Ford Foundation grants in photography, a fellowship at the American Photography Institute, a grant from the New York Foundation for the Arts and other important grants. The artist started her career as a fashion photographer which enabled her to build the foundation for her work as a strong visual artist. She was also chosen to participate at the Whitney Museum of American Art Independent Studies Program.

Cristinerose Parravicini: What is the relationship between your work and your body?

Renée Cox: In my work - especially in the earlier work such as in the Yo Mama series and the pregnancy series - the body has played an integral part. It deals mostly with female gender issues around the body and how the body is perceived. In those series I photographed the nude of

the pregnant body and showed it in a sort of a glorified light. I think this is a two edged sword because what I tried to do is to show the body in a glorified sense but also as it is going through this function of pregnancy which for some people historically has been something that has

been pushed away, put in the closet and not been shown with the exception of few painters such as Alice Neal. It was also a commentary on the art world and how the art world perceives the female artist as pregnant or with children.

CP: Do you think the perception of the body is going to change towards the new millennium?

RC: I think so. I would like to think so. Within the African American community I believe the change will be very slow because this community tends to be very prudish and conservative. But on a broader scale, the body has in a way "come out". We are seeing a lot of images of the body, we are dealing more with it. And if you look at youth culture there is also an intervention of the body itself through piercing etc. Today there is much more of an awareness of the body, it is

not something that is hidden anymore.

CP: Your older work is related to classicism, why that?

RC: You are talking about the Renaissance series. This body of work comes from my personal experience in studying art history during one year in Florence where I visited great museums and saw incredible art. My only problem with all that was that I never saw any people of color in

any of the artworks except for few exceptions where they where serving something. So that I decided to start from the beginning in the art history and take the original concept of Renaissance and fit it to the nineties by using people of color to represent the David, the

Madonna and Child, and Adam and Eve giving it a different spin. The grandiose feeling characteristic of the Renaissance work is reached by the scale of the works. For example, the David and the Yo Mama are seven foot photographs. This specific size gives even a more powerful impact on the viewers.

CP: Are there any cultural reference in your work?

RC: In the artwork that was part of the Black Male exhibition at the Whitney Museum It shall be named - which is basically a black crucifixion piece - I started dealing with Catholicism. In a way I was somewhat deceived. I started asking myself what was really the input of Catholicism onto slavery and how it operated, how did the Church in the 15th century made fortune off of it and why was the Church trying to figure out weather or not Africans were human beings. And then coming into the 19th century and looking at how the Jim Crow laws worked regarding the African

American hung on Sundays and Catholic slave owners. Those were the issues that came up while working on those photographs.

CP: Why is it important for yourself to be in your own photographs, in your own work?

RC: It gives more impact because it is very personal. I would not be able to find any body that would be able to portray what I really want to say.

CP: One of the most popular and most published of your photos is the Yo Mama, how do you explain this?

RC: The Yo Mama has a broad appeal particularly to women of all ages, and all ethnic backgrounds. It is an assertive and strong image of motherhood which turns against certain stereotypes of mothers as passive, helpless and victimized. It is about empowerment, there is a humor into it as well. Yo Mama is a towering self-portrait of myself naked except for a pairs of black high heels, holding my two-year-old son. The image of myself is both regal and erotic. This is a way for me to say "Girl you can put your pumps on, give your body a good line, pick up you child with pride and move forward." My statement hits a lot of women. Women have been conditioned to the fact that once they decide to have children suddenly everything in their life is supposed to stop. My premises is that you incorporate your child into your life and you continue to do what motivates you. The way that Yo Mama embodies the power of women is a pivotal force that moves our society forward. This progression is seen on many levels. As an African-American woman the Yo Mama series functions as a transcendence for racial issues: its universality appeals to women of all races based on the strength of the image. To me the image represents a powerful woman after pregnancy who was able to pick up her child in the quickest manor possible, still wear her stiletto's and keep on pressing. A digression of Yo Mama concerns itself with the play of ethnographical photographs such as Yo Mama goes to the Hamptons and The Feed juxtaposed to the colonization of whitepeople. These images concern themselves with the flip of art historical images with a new

approach on reality as we know it. The Virgin Mary, the most recognized icon in the world is now re-interpreted as a woman of color. This action flips the script of history as we know it:

re-inventing reality and history. Viewers now become forced to study their steady barrage of negative images and attitudes towards other civilizations, and conclude that tolerance and respect are essential for liberating the American nation of polarization.

CP: Is the Yo Mama's series also about eroticism?

RC: Yes. Yo Mama's masculinized stance in high heeled shoes defies gender stereotypes of woman as a yielding eroticized image of the heterosexual male gaze and desire.

CP: You have shifted references from the renaissance to the mutation of the body towards something new and more powerful about race, feminism and gender stereotypes.

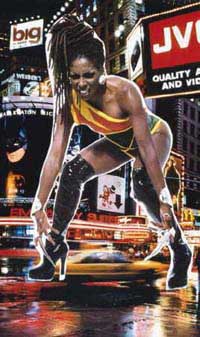

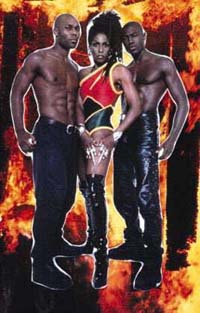

RC: The new work that is in process is really in line with the previous series of work. However, now I embrace the whole notion of the super hero, influenced by comic art and done completely

photographically and digitally. It is called Raje. It is the reincarnation of myself as a super hero. This character is a super hero who takes on the issues that plague African Americans and other minorities. Raje breaks and demands equality for all peoples who have been oppressed. The

character is illustrated taking on Napoleons army who once used the nose of the Sphinx as target practice. Raje liberates Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben from their boxes and a century of servitude and turns them into her allies and fellow super hero's. Raje takes Picasso to task for unright

fully borrowing and not offering credit for Cubism. Raje breaks the now evil symbol of the swastika. Raje confronts the record industry that has deceived so many youths out of their money.

Clearly this body of work exposes the ultimate truths and contributions, past and present that blacks have made in the United States. It also gives little girls and women a sense of empowerment while illustrating to the female population that she can do anything and go anywhere

without following the law of tradition and limitations. Raje is against any of the stereotypes, prejudices or misconceptions that are true within certain groups of people. Raje is a little fantasy and a lot of humor, and it should push people further to realize that we all have to let prejudices go. We are human beings and the skin color does not make a difference.

CP: The body is always present in your work and it is always muscular and powerful, why?

RC: Because I am interested to show that today women's body's are changing on a physical level too and I am an example of this mutation. The body image for women is going towards a major metamorphosis - from the voluptuous body of the beginning of the century to the strong, determined body of today's women. It is important to have a strong body for the daily chores as

well for the future to show the world of women empowerment and change. Women are going to start to claim their body for themselves and not letting men take control of it?