L'edicola digitale delle riviste italiane di arte e cultura contemporanea

Virus (1994 - 1998) Anno Numero 10 gennaio 1997

Jenny Holzer - Interview

by Florence Lynch

Mutation

LOIS KEIDAN

intervista di Franko B

n. 2 febbraio '98

Fear and loathing in Las Vegas di Terry Gilliam

Gianni Canova

n. 4 sett-ott-nov

Incontro con Lea Vergine

FAM

n. 10 gennaio 1997

Renée Cox

Interview by Cristinerose Parravicini

n. 14 ott-nov '98

Movimento lento

di Renata Molho

n. 14 ott-nov '98

Teddy Bears Company

Intervista di Antonio Caronia

n. 14 ott-nov '98

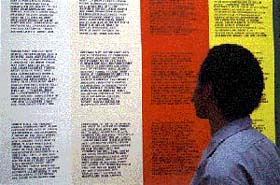

Incontro con Jenny Holzer, l'artista americana che lavora con il linguaggio, i segni, le parole. Nel 1993, durante le 'operazioni' di "pulizia etnica" nell'ex Yugoslavia, Jenny Holzer inizia a lavorare ad una serie di "scritture su corpo" il cui tema é la guerra e i corpi violati dalla pratica diffusa degli stupri di massa. La Holzer, che da sempre lavora sul linguaggio dei gesti, degli atteggiamenti, delle posture, trasmette messaggi subliminali: curiosità, chiusure, paure, timidezze... Sul nostro corpo é scritta la nostra storia e la storia del corpo sociale, quella storia che a volte fingiamo non ci appartenga.

Florence Lynch: The topic of your earlier work is an intimate part of our contemporary culture. Your words on child abuse, violence, and death have been heard since the eighties as unsparingly descriptive of the cries of those who suffered in silence. Now, as we get closer to the 21st century, these topics have become big public issues. This is the first time ever that all the presidential candidates have taken these topics and made them their own. How do you feel about the astounding amount of attention that these issues are currently getting?

Jenny Holzer: It's not a big enough public issue. I would think that the more attention given and the more solutions found, the better.

FL: Why did you choose to address these topics through an

advertising/media approach?

JH: Those approach works; in public people tend to look at electronic signs or television screens more than anything else. I try to place things where people naturally look. However, at the time I also used media that has nothing to do with advertising, such as marble.

FL: That's true, but marble had the same effect. The message was repetitive; it was about communication and advertising. It was searching for an audience.

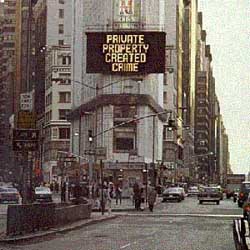

JH: At the beginning of my work I wanted to figure out how to put war, peace, sex, death and various other subjects in front of as many people as possible. So I first worked with street posters and then moved on to plaques that went on the sides of the buildings, then to electronic signs and on to a number of other media. I put things where there is a fighting chance that people will take notice of them.

FL: Do you feel that you took a Big Brother approach?

JH: It depends on the series. The electronic signs are Big Brotherish. The street posters were the opposite; they had the feeling of being very underground. Therefore, I deliberately played with the Big Brother approach; their content was different from the other series and the

message had a more official connotation.

FL: How do you choose certain issues and leave out others?

JH: With the first series I do not think I left out anything. The truth is I felt like I had covered every topic, from every possible point of view. The same with the "Inflammatory Essays," when it came to living and survival, again, many different things were covered; but I think you are right, for the most part I do not write about buttercups and butterflies. I gravitate to some tough issues.

FL: Is that deliberate? Are you really trying to get people to listen?

JH: Sure, but at the same time I think we cannot help but be ourselves; and we usually have to be honest about our preoccupation. What I present are mine.

FL: Let's talk for a minute about your audience. You do not only have an art viewing audience. You have done works in spaces where the casual passerby takes notice of your work while completely unaware of its artistic content. Is this you looking to attract the random observer or is that a byproduct of your work?

JH: When I work in public I work anonymously; so that people not only do not think about art, they do not think about the work as being the opinion of any one particular person. And yes, it's probably pretty important that the works in public are taken at face value and that people think about the literal contents of them rather than whether they are aesthetically pleasing. With the public installations the aesthetic, if you will, is to catch people's attention and hold it.

FL: How do you know the reaction of the casual passerby who has no way of communication to you what they think about what you're saying.

JH: Oh they do have a way of communication to me. People tend to write all over my street posters. So I just poke around and collect that information. Also, I would and still do stand around and watch the crowd's reaction when I have something in public.

FL: So that's your way of watching the viewer's reaction.

JH: Or lack thereof. That's one way for me to get feedback. But you are right, for the most part with the public installations there is not that direct contact which for better or worst I have with the gallery exhibitions.

FL: I presume that you also get a media reaction.

JH: Sometimes.

FL: Sometimes? Positive, negative?

JH: Both; but it all depends.

FL: What about your recent ventures into the world of tattooing. You had some works in Basel on tattooing.

JH: They were writing on skin; they were not actual tattoos.

FL: Was that the idea, that one would think they were tattoos. I certainly thought so.

JH: I wanted to create an illusion. I had hoped that people would consider what happened in the concentration camps when the prisoners were numbered; or that they might think about jail house tattoos. But the main idea involved having these particular texts about rape and murder on the

skin because rape is the crime against the body. I wanted to be literal and write these texts on various people's skins.

FL: Are you also writing on your own body?

JH: No, I was one of the people who wrote the text. My hand was one of the voices. There were six of us when we did the photographs-- three German and three English speaking people. I wrote some of the English text. But there were three women upon whom we wrote.

FL: Tattoos were traditionally know as a macho symbol and it is only recently that it's no longer associated with rebels, bikers and gang members. And one of the criticisms about your work is that you articulate feminist rhetoric. What is the connecting point?

JH: All I can do is tell you what I was thinking when I chose to write on the body. I wanted to insistently refer to the fact that rape is not some type of abstract crime, that it is something that actually happen to people's bodies. I wanted to present it as the "abuse of touch" which in fact it is. So that's why I went to the skin. I did not really think about tattoo as being a macho thing, although you are right. Tattooing for the most part is or at least was done on and by men. Perhaps, that assumption is not a misfit-- rape for the most part is a crime committed by men.

FL: This venture is almost your intrinsic way of being subversive and revolutionary in your reaction toward that act. Incision on the skin, as it was done in the concentration camps, was a moral crime; and tattooing at one time was not accepted by society.

JH: It was my way of being outspoken about the crime and acknowledging its existence.

FL: This is not a body of work that's known in New York; however, it's known in Europe.

JH: Yes, it was done in Europe and it has not been seen much in New York. I showed it briefly at Barbara Gladstone but it's much better known in Europe than in the States

FL: Is it coming to New York?

JH: I showed a virtual reality version of the "Lustmord" series at the downtown Guggenheim a couple of years ago but I have no plans right now for bringing it back to the States. However, I do plan to do a show of that work here in Switzerland. That's what I have spent a week here doing. This may be one of the last places I show it.

FL: You're showing it in video format or photographs?

JH: Here it's human bones and electronic signs.

FL: Is it real human bones?

JH: Yes.

FL: When did you start to work with bones and why?

JH: To tell you the truth I cannot recall the exact moment or how I came to it. I was trying to be literal about the crime of rape and murder; and once the crime is concluded bones are what's left. I thought they might be evocative. I did a project for a magazine and at the time I had just started to write the Lustmord project. For similar reasons we applied the concept of the Lustmord series by creating an imagery on the cover of the magazine which was made from women's blood. I wanted to keep insisting that blood too was part of the crime and that it had to do with

the body.

FL: Were you using the blood of victims?

JH: It was a combination; some of it is the blood of victims and some of it is not. Some victims had volunteered along with a group of Yugoslavian women who were not victims.

FL: The bones are also of victims?

JH: I do not know who the people are.

FL: Are you also interested in the internal mechanisms of the body? For example how the body breaks down or how it heals?

JH: Sure, the older I get. Yes, I'm interested in the brute physical aspect and of course the psychological as well.

FL: So where you once worked on a slate with words, you are now working on a totally different type of surface: the body, skeleton. Where does this desire to escape from the canonic space that

you have always worked on come from and where does it lead?

JH: For the last few years I have from time to time relied on non verbal means. I did a "black garden" in Germany where much of the piece is sustained by very dark plants and benches with writings on them. But for the most part it was the dark plants that held the piece together. Also

in some of the Lustmord exhibitions I use the bones with just a little bit of writing on them; mostly they stand for what they are independent of the writings. Even with some of the electronic sign installations in museums or galleries the strength of the pieces I think have to do with the rate at which they flash and what impact the flashing has on your body. The fact that the rooms are darker and that the text rises, that physical aspect is an important part of the work, not counting the verbal impact.

FL: Can you tell me a bit more about the "black garden" and is it a work in process?

JH: Because it's a garden it will be ongoing. In fact, I will need to spend some time on it this season. The layout of the garden is done and it's fully planted, but you have to keep working on a garden to get it right. The benches are finished and in place. But I would like to visit it again next spring to see what should be added, subtracted or moved around. I will talk to some plant breeders and see what new black plants are out there.

FL: Where is it exactly?

JH: It's in the North of Germany in a little town called Nordhorn; close to the Dutch border.

FL: You're working on several other projects in Europe, what else are you preparing now?

JH: Right now I am working on a Lustmord show in this Carthusian monastery. The installation is in the cellar of this ancient place. It's a great place to put bones. Then I will be going to Florence to do a project for the fashion biennial. I am partnered with Helmet Lang and we're to

do something in a pavilion there.

FL: With these projects has your art become one of images and objects rather than words?

JH: I think the words are probably still the foundation of it but there are important components of the work that are non verbal.

FL: Do you have a project ready for the fashion biennial?

JH: Oh, vaguely. Ready, that's probably too strong. The biennial as a whole does not seem to be ready.

FL: Are you doing something on the theme of fashion?

JH: I don't know anything about fashion. I'm probably one of the least fashionable people in the world. I found a text that I had written for an AIDS fund raiser and I am going back into that text because I find that it had to do with putting on and taking off article of clothing, what you do naked or clothed, and what you do with clothes after someone dies. In that area I can wander around because I know what's doing in that sort of territory.

FL: Would you consider your work now to be more creative or instinctive?

JH: For me it would and should be both simultaneously for the work to be at all complete.

FL: What would you say is the role of your art?

JH: Oh that's one of those unanswerable questions. I have pondered over that one for a long time. It's to present what I believe needs attention or redress in a way that the appropriate emotions are attached to it.

FL: And what are those appropriate emotions?

JH: It depends on the subject but to use Lustmord as an example: fear, grief, outrage, things like that.

FL: So you are looking for outward emotions, not just an internal response, but a physical reaction to your work.

JH: I want people to consider the matters that I present to them and I hope that once they do they will have some foundations for action. I suppose that in the process of considering these terrible subjects they would have any number of emotions but I would not want to prescribe them.

FL: Your work expresses very real qualities. Following the narrative of your works over the years one encounters a number of feelings: strength, oppression, hopelessness. At times it is even feels lyrical or poetic to some people.

JH: The first thing that occurs to me is that I certainly wish I was a better writer. I suppose some works are more or less lyrical. I make no claims to being a poet. I write as well as I can and what I write is adequate to the task. I would not want things stripped of their visual components. That part is important not just for amplification but for the meaning of the work. Some of the writing I think is somewhat imaginary-- you can picture things as well as feel them; but again I am pretty sure it's not poetry.

FL: Would you say that your work is political?

JH: In a large sense, may be. It's not didactic.

FL: Your work is social in a very public sense. It's certainly addressing the public. It's talking to everyone. Do you feel that you are also talking to the government. Are they listening?

JH: Well, I know I'm talking, I don't know whether they are listening. I guess I could get my files and see.

FL: Your files?

JH: Don't most of us have files? That's a sure way to find out if someone's listening.

FL: I don't know if that's the best way. In your work you have addressed issues of cruelty, violence, abuse, death and you have taken a tautological approach with these voices. Will you

continue to address these issues or will you move on to others, if so what are they?

JH: I am never quite sure. I do not have a program as such. I seem to be trekking around the idea of writing something about incest and or child abuse. Since I have just started, I am not sure how that will develop. Until I am in the middle of it I usually do not know what the next body of

work is going to be.