L'edicola digitale delle riviste italiane di arte e cultura contemporanea

Flash Art Int. (1999 - 2001) Anno 33 Numero 210 January-February

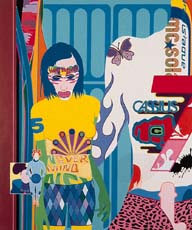

Beautiful Dreamers

Grady T. Turner

Emerging American Painters

Franz Ackermann

Wolf-Günter Thiel and Milena Nikolova

n. 216 Jan-Feb 2001

Shangai Biennale

Satoru Nagoya

n. 216 January-February 2001

Aperto Albania

Edi Muka

n. 216 January-February 2001

Cecily Brown and Odili Donald Odita

n. 215 November-December 2000

Cai Guo-Qiang

Evelyne Jouanno

n. 215 November-December 2000

Aperto New York

Grady T. Turner

n. 213 summer 2000

Was there really a time when painters worried about the relevance of their medium? These days, the once-ominous "death of painting" is an in-joke among artists who were still watching cartoons when Julian Schnabel broke crockery and Robert Longo had long hair. For many emerging painters, cartoons still matter more than their immediate predecessors.

Despite anything you may have heard to the contrary, painting remains as hip as video and digital media among emerging American artists. But make no mistake: this generation raised on computers, cable television, and video games has radically changed the rules when it comes to art's most revered medium.

Traditionalists can decry the rapid-fire visuals of the Internet and MTV just as another century scowled at Nietzsche and Darwin, but like it or not, the esthetics of popular media are continuously absorbed into painting. Pop culture provides the common ground among diverse young painters, who generally share predilections for Surrealism, sampling, psychedelia, science fiction, fashion, and porn. Few claim any interest in politics, transcendence, or making sense.

The fact that beauty, craft, and form are important to newly established stars like Michael Bevilacqua, Inka Essenhigh, Lisa Ruyter, Fred Tomaselli, and Barry McGee has not been lost on emerging artists. Once unfashionable, esthetic criteria are once again taken for granted. Even so, don't look for anything resembling a coherent movement. Untroubled by another generation's ideological battles, painters now seem more concerned with synthesis than categorization, easily

transgressing and reshaping the boundaries between abstraction and figuration, expressionism and minimalism, irony and meaning.

Recalling Jackson Pollock's desire to be "in the painting," Giles Lyon begins work by spreading canvas on his studio floor. When a canvas is sufficiently soiled by his comings and goings, Lyon works into the random shapes left by footsteps and grime, painting stringy lines that accumulate to suggest gooey viscera. If his process seems to negotiate between chaos and order, Lyon gives order the upper hand with an esthetic fed by Philip Guston, medical illustration and manga comics. His most recent work recalls Rorschach tests, handily turning an analyst's tool into a riff on his own graphic facility.

Tricia Keightley is similarly fixated on entrails, though her sense of the body's interior is informed by garage sales more than medical manuals. Like a Victor Frankenstein forced to make do with suburban detritus, Keightley constructs plausible organic systems incorporating the stuff found in the garage: an inner tube, a toilet paper dispenser, a woven plastic lawn chair.

More accurately, Keightley hints at specificity in her references to material reality, but she leaves it for us to determine the degree of representation in her abstraction.

In his allusions to the body, Andy Collins fixates on joints, gaps, folds of flesh and other sites where negative and positive spaces meet. Mixing alkyd into his oil paints, Collins layers pastel colors into milky smooth surfaces in which edges dissolve and colors melt into one another.

In fields of such translucent elegance, a composition resembling a hip joint becomes luxuriously sensual, as tactile as the sense of one's own hips moving, as soft as a Dreamsicle melting on the tongue.

Speaking of art that melts in your mouth... for the past few years, Martha Benzing has been perfecting the craft of painting with pigments derived from M&Ms, Kool-Aid, and other sweets.

The candies once appeared as collage elements as pontillistic dots of artificial colors. But in her recent work, Benzing has developed a surprising range with limited materials, so much so that critics now compare her pigment-on-silk stains to Morris Louis and Helen Frankenthaler without a hint of irony. As she has become increasingly accomplished in her technique, Benzing has also grown more confident about scale, now using Milky Way candy bars to evoke the solar system. Walking a fine line between painting and sleight of hand, William Wood works in a mysterious process that leaves viewers certain they are looking at the artist's gestures even as they ponder his means of production. Working in grisaille, Wood achieves a photographic range of gray tones. Curvaceous lines swirl and overlap to create an illusion of depth. Organic patterns suggest the textures of bone marrow, blood cells or muscle tissue. But the scale seems equally infinite and microscopic: are we contemplating the intricacy of cells or the vastness of a cosmos? Nina Bovasso stays close to earth, compiling her abstractions in brick-like capsules piled heavily upon one another, or in swirled lines with the ordered chaos of a freeway cloverleaf.

Cartoonish lines and closed environments recall the late work of Bovasso's inspiration, Philip Guston. With wit and painterly smarts, Bovasso finds her subject in hand-made systems that seem purposefully out of step with postmodernity.

Indeed, many artists have abandoned heroic gestures for more introspective modes in which originality seems a dubious, if not impossible, aspiration. Graham Gillmore's richly layered paintings break thoughts into phrases and words that are trapped in balloons tethered to one another by tenuous strands. Defying viewers to reconstruct meaning from his errant logic, Gillmore loosens meaning from its moorings to float on a sea of free associations.

Ruth Root turns abstraction into her own private playground with paintings that might be summarized as neat stacks of rectangles and squares were it not for her capacity for variety and humor. For a recent show, Root painted dozens of paintings with miniature cigarettes wedged between edges of abstract forms, as if the paintings were contemplating the painter rather than the reverse.

Outfitted with oil paint, markers and wit, Root exercises a vigorous talent for mixing high and low. Like McGee, Phil Frost appreciates the aura of found artifacts even as he defaces them. Subdued colors are often submerged behind the flat white of intricate designs painted with Liquid Paper. Arcane symbols and elongated totemic figures cover the yellowed surfaces of worn wooden bats, vintage Marvel comics or sheet metal, suggesting the syncretism of Wilfredo Lam or Jose Bedia with the secular relics of a slacker's childhood. As the art market continues to enjoy good health, it's common for galleries to show painters fresh from art school; many artists now land galleries before finishing their degrees. Given the money floating around, it's no surprise that artists are more collegial that cutthroat these days. It's invigorating to hear artists in their twenties enthuse about the thirtysomethings whose success they hope to emulate.

But every now and then there are murmurs of unrest - that show was too pretty, this artist is too hung up on style - that suggest there may be a mild backlash brewing against the current infatuation with beauty. So long as the cash registers are ringing, the art world may simply find a few more punks in their midst in a few years. If the market heads south, then beauty beware: the infidels are already at the gate.

But for now, put aside any misgivings with a champagne toast to the continued vitality of painting. Enjoy this fin-de-siècle decadence - I'm sorry, I meant to say "open-mindedness" - for as long as it lasts.

Grady T. Turner is Director of Exhibitions at The New York Historical Society.